What Is Primitivism and How Did It Affect the Art of the Early 20th Century?

When asked to provide an article about art and race for infinite mile, the topic seemed very natural. Equally an fine art historian from a multicultural background, I have always approached the written report of history with a critical middle. The particular topic of Primitivism, which was a 19th-xxth century artistic movement developed past prominent European artists: Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, to name a few, was marked by European artists breaking away from traditional western creative conventions in favor of the curving, geometric, and/or flattened forms attributed to some African, Oceanic and Native cultures. As a graduate student, the topic fascinated me. Heavily focused on the written report of the art and visual culture(southward) of Africa and diaspora, my graduate experience centered on the deconstruction of traditional notions developed during periods marked past racism and colonialism. The Primitivism exhibit explored in this essay, for example, illustrates a contemporary manifestation of age-old perceptions of the African, afro-diasporic and indigenous domains.

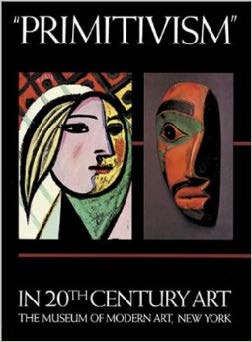

| figure i |

|

| Picasso, Girl before a Mirror, 1932, and Kwakiutl half-mask |

The importance of the 1984 Primitivism exhibit at the MOMA is in the understanding of its conception: by establishing the geo-political histories in which racist ideologies were bred, we can go a step further from dispelling derogatory terms like "primitive" and dig into the analysis the bodily exhibition and displays as expressions of such ingrained ideologies. Understanding the Primitivism exhibit: the proclaimed innocence of the directors, the lack of regard for the context of of non-western objects, and the compliance by the museum itself to host such an exhibit teach us tremendous lessons almost how we treat art and race in the west. One such notion, which often prevails historical narratives, is the focus on fine art equally being western, and furthermore, that not-western visual culture is meant to facilitate the understanding of western art.

This deep-rooted Euro-axial notion of non-western visual culture equally secondary to the fine art of the due west is something I hope the reader gains awareness of through the critique of Primitivism. Looking critically at places like the Detroit Establish of Arts, for example, reveals a fix of questions: where are the non-western collections placed in the museum? How are these galleries lit? Why are the European galleries centralized, brightly lit and the most easily accessible? What exercise these design decisions imply near the fashion nosotros view the w in relationship to other cultures? At trusted institutions such as art museums, the treatment of non-western vs. western art must be carefully considered. I promise, if annihilation else, that the average museum-goer will think critically the next fourth dimension they enter a gallery: why are they seeing what they see, by who and how such decisions were made, and nigh importantly: what implications the decisions fabricated by the museum produce.

| figure 2 |

|

| "Primitivism", Dallas showroom |

In 1984, William Rubin curated an showroom entitled "'Primitivism': Affinity of the Tribal and the Mod" at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which subsequently traveled to Dallas and Detroit. The exhibit aimed to juxtapose "primitive arts" from the African, Oceanic and Native American Indian cultures with the arts of Mod Western artists such as Pablo Picasso and Paul Gauguin in club to express the supposed affinities that the latter group of works had for the former. The seemingly and absolutely innocent installation amassed major criticism from the public and art history world alike for, among other things, its utter disregard of the problem with the term "primitive". In a sort of pre-emptive strike, Rubin's addressed potential critiques of the dated terminology in the introduction of the lengthy, two-book catalog for the exhibit. The vibrant, elaborate catalog featured essays discussing the Western, Modern artists and their works with various images of African, Oceanic and Native American objects placed strategically in order to suggest resemblance or "affinities". His statement regarding the use of the word "primitive" recognized the sensitivity to the consequence, though Rubin's fundamental defence force was that the give-and-take merely referred to a stylistic, Western moment in art history which actually exalted the "tribal" rather than demeaned information technology (Rubin, 5). In fact, the curator's vision was that the exhibit should practise nothing more than than display the splendor and beauties of both categories of art—both the Modern and the tribal (Rubin, 1-7). Rubin's aim was to visually obsess the audience with hitting "affinities"—by hanging the works of the Modernistic masterpieces aslope the works of the "archaic" objects, Rubin wished to illustrate a "mutual denominator" in the objects and paintings (Clifford, 193). By considering the artworks and catalog of the 1984 MOMA exhibit entitled "Primitivism" In the 20thursday Century: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, it remains clear that the exhibit failed as a substantiated lesson in art or history and instead effectively propagated an "us vs. them" mentality, which prevails art historical research. Through the use of carefully structured rhetoric juxtaposed with Western works of art, the showroom produced an exoticized "other" in its tribal associations and, furthermore, extended a human relationship of superiority between the "modern" West and elsewhere. The brandish of arbitrarily chosen "tribal" items confronting a backdrop of master Modern paintings proves that the thought of an exhibit every bit vague and oblivious equally "Primitivism" had no intentions of educating and dispelling misconceptions of the Black and indigenous continents. In fact, the opposite occurred, in that the exhibit itself perpetuated outdated ideologies by reconstructing the imagined inferior earth of "primitives" as a legitimate reality.

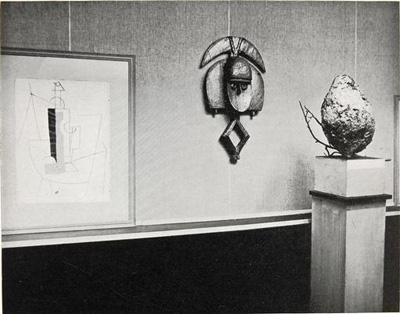

| effigy 3 |

|

| "Primitivism", Dallas showroom |

The fundamental problem intrinsic to the Primitivism exhibit conducted past William Rubin was that it explicitly treated the arts of the "primitives" as mere facilitators in the realization of the therefore "true" Western art both symbolically and visually in its placements and discussions. This idea was synthetic visually; the exhibit was divided into four singled-out sections: Concepts, which aimed to found the modern response to the influx of tribal objects through the use of examples. This section seemingly prepare the tone for the entire tour by introducing the viewers to the idea that Modern works contained "archaic" influence. Next was History, which honed in on the direct influence of tribal arts on Modern painters and sculptors. This section juxtaposed "works of modern art from the turn of the century to almost 1950 with tribal objects" said to have influenced the works (Clifford, 212). The credible aim of this display was to build on the Concepts section and further legitimize the claims by citing "direct" influence. Furthermore, the Affinities section presented "a grouping of superb tribal objects notable for their appeal to modern gustatory modality". These juxtapositions were chosen exclusively to illustrate to the viewer what Rubin referred to as "bones mutual denominators" of the works (Clifford, 193). Once more, the Affinities section seems to function every bit a sort of peak of the exhibit, where juxtapositions were even more precisely chosen for the purpose of driving the original merits domicile—that the Modern painters were absolutely influenced past tribal objects—and the proof of that tin supposedly be seen in the visual displays of questionable resemblances (Clifford, 193). The fourth and final department of the exhibit was labeled Contemporary Explorations and featured Western art afterwards 1970 which was said to take been inspired by the techniques and mentality of "primitive" cultures. The press release at MOMA theorized, "structures of myth and cosmology here combine with a primal sense of fine art-making activity to embody a strongly altered but still vital bond betwixt modern and tribal creation". Remarkably, the entire showroom held a total of 150 Modern works with over 200 tribal objects accompanying them—over half the exhibit composed of the "tribal" (MOMA, "New Exhibition", 2). Although the tribal objects outnumbered the Western pieces exhibited, it is clear that the overall tone of the showroom was set as being strictly Western by including but non examining the tribal objects which made up over half the installation. As the itemize stated, the objects included were viewed as an ''aspect of the history of Modernistic art, not of tribal art.'' This statement openly categorizes the objects equally Western, with the understanding that to be considered equally art they must first be qualified as modern (and therefore Western). Furthermore, the argument openly asserts that the showroom is not purporting whatsoever claims on the history of tribal art—instead, the inclusion of the objects are meant to fortify explanations of the Western artworks. The danger in this tonality is an argument that relies on a modus operandi which inadvertently maintains the supposition that fine art is only Western—and therefore, the West solely determines what is to be categorized as fine art under this association. To elaborate, the mind frame of the exhibition functions from the perspective that, once the Modern artists deemed the tribal objects as their so-called muses, then and only then did the objects become "fine art". The objects' credible influence on Modern artists exalted them to the level of "art"—but only as they pertained to the modern works themselves—an even greater inadvertent proclamation of cultural superiority (Clifford, 195). Once a viewer reads between the lines, and so to speak, at the seemingly innocent exhibit, these presumed to be outdated views expose themselves every bit operating alive and well in contemporary times, and furthermore, at such inherently trusted educational institutions as respected equally the MOMA.

| figure 4 |

|

| "Primitivism" exhibit, MOMA |

The near prominent issue raised by the Primitivism exhibit was the lack of contextualization of the objects, speaking farther to the idea of their role in the showroom equally facilitators in the realization of the magnificence of the Western works (Harney, 1). Leaving information such as the definitions and functionalities of the tribal objects out of the contextualization of the showroom leaves them to deed as a sort of wallpaper in the prove. Rather than include specific essays or even abbreviated label descriptions in lodge to provide a framework for basic cultural, historical and/or aesthetic understanding of the objects, Rubin decided the objects' history an unnecessary aspect of an otherwise solely Modern prove. This brings united states to the next point of contention in the exhibit: the thoughtless decontextualization of the tribal objects through purposeful omission of discourse on their meanings and uses; instead strictly categorizing them as "art", but as stated earlier, only when relevant to the Modern works (Kramer, 2). This point is clearly underscored by Rubin's own access; he states in the catalog that the exhibit's goal is to ''empathise the Archaic sculptures in terms of the Western context in which modern artists 'discovered' them'" (Rubin, 1-4). The syntax of this single phrase alone reveals many problems concerning objective, historical research: aside from making no attempt to deconstruct the derogatory term "primitive", Rubin openly states the goal of the exhibit was to examine Western works inside a Western context nether the supercilious assumption that the West 'discovered' the indigenous worlds (Clifford, 196). Whether information technology refers to fine art, civilization, objects or societies, the rhetoric clearly reflects that of an outdated ideology—1 which extends a relationship of ability over the indigenous peoples in its misguided desire to construct a primitive muse for the Modern artists. This idea of a homogenized, inferior people exhibiting mystical, romanticized cultural stereotypes to be used equally a Westerner's muse was not a new idea—first made pop by the Orientalists, this manner of expression enchanted Westerners with imagined landscapes of the Arabian peninsula or sensual renderings of nighttime haired, hr-glass figured harem women. Images such as those served as entertainment in that they fed curious European minds with fantastic amalgamated images of another earth. The trouble, yet, was that the images were essentially stereotypes—though positive in some regards, every bit in the obviousness of their focus on beauty—notwithstanding were stereotypical and lacked explanation or substance. Without caption, these images of the Arab world would go along to dominate media stereotypes for hundreds of years, though to the W they functioned and continue to office as amusement. These unsubstantiated images of "other" cultures seem to intentionally silence them and then they may serve their fantastic, romantic purpose. This notion is not lost at the Primitivism exhibition—woodcarvings and masks echo the being of a not-real primitive world (Clifford, 200-201). With no caption, they get the perfect mood-setting ambiance for the Western globe—evoking only not exploring in detail—safe from the realities of the indigenous worlds yet free to have pleasure in them (Kramer, 2). The idea that the "other" worlds are non the trouble of the west unless they pose some sort of benefit—whether it be aesthetic or economical—roots itself in colonial attitudes of cultural superiority (Harney, ane). The idea that the indigenous did not exist earlier the west considered them relevant resonates this royal attitude which subsequently prevails the entire catalog for Primitivism. Though seemingly innocent in his endeavors, Rubin explicitly perpetuates a Euro-centric, culturally insensitive and exclusive mentality that the field of art history has however to completely overcome. The fact that Rubin seems to operate from a place of skilful intentions but an outright disinterest in information or the relaying of it further befits the colonial narrative from which the exhibition was conceived.

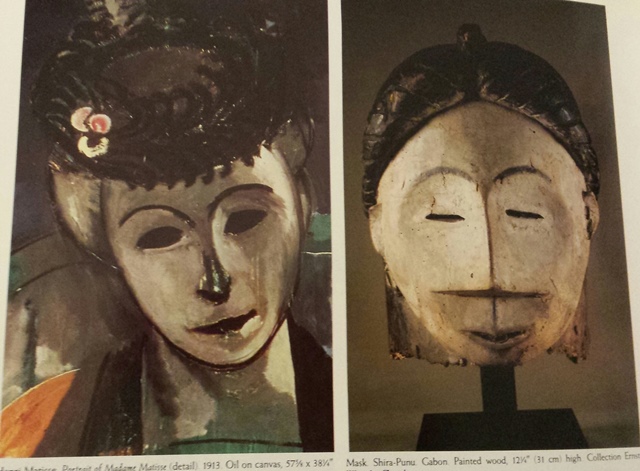

| figure v |

|

| Matisse, Portrait of Madame Matisse (detail), 1913 and a Gabonese republic Mask placed side past side, "Primitivism" Catalog |

To illustrate this betoken, one may investigate the utilise of the Dan masks, which patently were a favorite of the works displayed throughout the Primitivism exhibit. Co-ordinate to Robert Ferris Thomson'south Wink of the Spirit: African Afro-American Fine art & Philosophy (Vintage, 1983), these tribal masks exist in several African sects such as the Dan, Yoruba and other masquerading cultures of Western Africa. The masks are primarily used in dance every bit a means to physically embody the spirit of the Ashe—a term used to refer to the divine spirit—the mask holds corking sacred power and is not meant to be seen outside of the masquerade. The masquerade itself is a wholly spiritual result, taken very seriously by the community and only danced by highly trained, initiated members of club. The rituals involved in the deliverance of the embodied spirit are highly organized and intricate, every bit to not offend or disappoint the Ashe. Though they are entertaining events, nonetheless, these religious practices are prepared for time in accelerate and contain strict rules of conduct and adherence. During the masquerade, an initiated dancer becomes transformed or "possessed" past the Ashe, embodying the characteristics of the spirit through movement (Picton, 191). The dancer is so understood to be the mask and no longer a human— the vessel delivering the spiritual earth to the viewers with the mask acting as the concrete presence of the spirit (Thompson, 3). Without the masquerade and the transformation, the mask is rendered useless, lifeless and meaningless by gild. The important distinction to be fabricated is that the mask is non understood every bit fine art by its people—significant, it is not created by the craftsmen for pure aesthetic value (Picton, 191). Instead, it is created with the intent that information technology would deed every bit the embodiment of the spirit past both representing the divine every bit well as separating the spiritual and human worlds—by literally masking the eyes of the human being then as to not crusade interaction or intimate oversupply engagement (Picton, 187-eight). The mask is therefore a sacred object holding intrinsic strength according to masquerading cultures such as the Dan and Yoruba (Thomson, 3). Furthermore, to the masquerading cultures, the mask should not be viewed exterior of the masquerade as it is sometimes viewed every bit a crime confronting the spiritual world. This hugely disrespectful deed may render every bit a punishable offense amongst societies in Africa—important cultural data and notions that are ironically if not blatantly lost in museum exhibits such as Primitivism. Descriptive cultural context such as that regarding Dan masks are completely undermined and disregarded throughout the exhibit in an explicit desire to attach to pure artful weight in regards to the objects—a notion that does not extend itself across cultures, which further substantiates Primitivism equally a culturally exclusive experience.

| figure half-dozen |

|

| Objects and paintings, Dallas exhibit |

Finally, and probably most plainly, the museum blundered by insolently utilizing dated, culturally insensitive rhetoric in the catalog, championship and texts of the exhibit besides equally displaying cultural materials caused through questionable practices (Clifford, 189). The only indication of the desire to dispel misconceptions of the indigenous world is plant in the quotation marks encasing the give-and-take primitivism in the title of the exhibition. These quotations at starting time seem to elicit questioning of the term and offering the visitors an indication of farther investigation to follow—however, the suggestive nature of the quotations are despondently where the interrogation of the insensitive expression ends (Kramer, 1). This lack of discourse moves from beingness passed off equally mere omission of information to existence understood equally utter self-indulgent ignorance once Rubin's essays regarding the use of the term are relayed. Throughout the catalog, Rubin propagates the imagined inferiority of the tribal world—using demeaning characterizations such as "naïve", "kid-like" and "uncomplicated" to depict both the cultures of the tribal and the works they produced (Rubin, ii). These terms are arguably more offensive than the defense of the discussion archaic in that information technology openly adhered to a perspective of the African continent as being less-than and innocently underdeveloped every bit civilizations relative to how the w viewed itself. The uses of said terms in the catalog beg the question: how was information technology that in the mid-1980s, terms similar "naïve" and "simple" would pass every bit adjectives to describe historically subjugated peoples in a itemize for a major show in one of the cultural hubs of the world? Rubin dedicated his argument past asserting his perspective of the cultures and their works strictly as admiring and esteeming, though his catalog rhetoric clearly reflected a psychological position grounded in Western cultural superiority. Rubin attempted to outline the fascination of the Modern artists with the African, Oceanic and Native American cultures using the characterizations of unproblematic, naïve, and kid-similar and in turn effectively portrayed the West equally the requisite antithesis of these worlds—for the naïve, the Westward is wise; for the child-like, the W is experienced; and for the simple, the West is complex. These unspoken proclamations resonated within the exhibit—a danger when the primary constituencies of the exhibit were Westerners themselves. When trusted institutions such as museums pose conjectures, they are accounted to be truth by the general public and therefore hold greater responsibility in providing all facets of a story as best it can. One time the MOMA chose to exhibit Primitivism the fashion Rubin envisioned, information technology thereby propagated the outdated ideologies and cultural insensitivities as truth, effectively projecting erroneous ideologies onto yet another generation of museum visitors. Rubin'south patronizing attitude was further reinforced by his insistence that the exhibit was celebrating the "primitive" rather than deriding or marginalizing the cultures of the indigenous. However, this point is proven nothing by the mere acquisition history of the objects at mitt—it was no mystery that the bulk of the objects in the exhibit were acquired from said cultures during periods of colonization of the continent (Kramer, 6). Many of the original objects obtained from the tribal worlds and used in the exhibition were acquired during a fourth dimension of forced "European political, economic and evangelical dominion" over the African earth (Clifford, 196-seven). Notwithstanding, this circuitous aspect is clearly left out of the Primitivism bear witness; though their belonging to prominent collections both private and public tend to speak to a civilization of domination where an inadvertent influx of cultural objects from Africa became readily available to the West. These questionable origins and practices further rescind Rubin's Primitivism as an innocent look at beauty and art.

Primitivism traveled to the Detroit Institute of Arts the following year (1985), where it was received with mixed reviews. David W. Penney who served as the Assistant Director of African and Oceanic, and New Globe Cultures at the Detroit Found of Arts summarized the central issue of Rubin's exhibit in a concise and eloquent style:

The Western notion of "archaic" peoples is a longstanding myth that views conflicting, exotic cultural forms as living relics of an bequeathed by. The MOMA catalogue presents tribal art purely through the eyes of twentieth-century civilisation. This viewpoint defines "primitive" art every bit a category. The exhibition and catalogue themselves are important in the ways they re-shape our evolving concept of "primitive" human being--at present seen as a nameless, faceless Picasso of the bush. (Penney, 91).

Penney'due south sentiments accurately outline the problems of the exhibit while expanding upon the concept itself—non merely does Rubin re-introduce the concept of "primitivism" to the public, just continues to develop the Western public's perception of it. In this manner, Rubin pushed the old ideologies forward by giving them new life and assigning to them new associations and characteristics through the visuals of the catalog and exhibit.

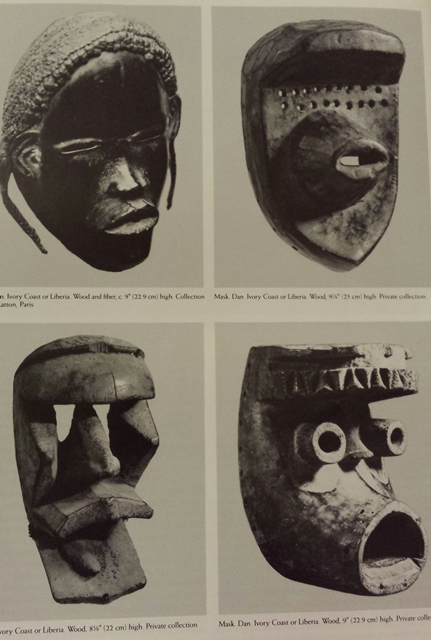

| figure 7 |

|

| Dan Masks, "Primitivism" Catalog |

| figure viii |

|

| "Primitivism", Dallas exhibit |

| figure 9 |

|

| Tribal objects, Dallas exhibit |

| effigy ten |

|

| Paintings and tribal objects, Dallas showroom |

With all of the criticism of the Primitivism show in heed, the question now begs: what would be an advisable brandish featuring the objects and artworks of the indigenous worlds? Exhibitions such as those conceived by Rubin undoubtedly come nether fierce critique due to an ever-changing and always-expanding globalized vocalization in all fields of academia. As stated, it is not the title of the show that offends but the determination to not explore and debunk the term paired with the deliberate condone of the bodily objects in the show that sparked controversy. Rubin is technically correct in stating that the term "primitivism" refers to a moment in Western art history—this statement is all that is needed to understand the decision for the championship. However, had he brought in African art history scholars to contribute to the shows essay catalog in significant ways, what would that have done for the merit of the show? For one, it would have broadened the word and included a voice and caption for an unabridged continent of objects which in this context are misunderstood. Furthermore, it would in the very least take rendered Rubin and/or the MOMA every bit interested in the pursuit of broad cultural discourse rather than the complacent bear witness it produced. Had they attempted to critically re-examine the past rather than re-innovate old ideologies, Rubin and MOMA would take been critiqued quite differently—based on their attempts and effectiveness of opening discussions rather than the lack of cultural sensitivity. Together these factors contribute and bespeak to a museum installation conceived under an outdated, arrogant schoolhouse of idea which artlessly operated from a mentality of cultural dominance of the West, and furthermore, defended itself under the guise of mere aesthetic admiration and beauty. William Rubin's annunciation that the objects were to be viewed merely as "cute art" inspiring the fine art of the West not only asserts a position of dominance over indigenous cultures, but also relinquished his intellectual responsibility to the non-Western objects in his exhibition. This was specifically accomplished by claiming that the objects were meant only to be viewed and not thought about. To display these objects without regard for their meaning, obtained under the questionable circumstances of colonization, explained only in terms of the Western fine art they helped produce, and furthermore described equally belonging to such derogatory realities as those who are "primitive" tin can only be interpreted every bit a blatant disrespect and disregard of unabridged cultures of people; further 'othering' and perpetuating stereotypes of the ethnic worlds. It is for these reasons that Primitivism in the 20th century: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern fell short in operating as an objective, cross-cultural dialogue meant to bridge civilizations and their arts in an endeavor to foster a rich agreement of the earth and its complex histories.

Works Cited

Clifford, James. "Histories of the Tribal and the Mod."

The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. 1st Ed. Cambridge: Harvard Academy Printing, 1988: pp. 189-215. Print.

Harney, Elizabeth. "In Search of Africa in New York and London".

Blackness Renaissance. New York: Institute of African American Affairs, 1997. Impress.

Kramer, Hilton. "The Primitivism Conundrum". The New Criterion. Vol. 3, 1984. Print.

"New Exhibition Opening September 27 at Museum of Modern Art Examines 'Primitivism' in 20thursday Century Art". The Museum of Mod Art, 1984. Press release.

Penney, David Due west. Rev. of "Primitivism" in 20th Century Fine art: Analogousness of the Tribal and Modern, by William Rubin. African Arts. August 1985: p. 91. Print.

Picton, John. "What'southward In a Mask"? African Languages and Cultures. Vol. 3, 1990: page 181-202. Impress.

Rubin, William. Ed."'Primitivism' in 20thursday Century Art: Analogousness of the Tribal and the Modern." New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984. Print.

Thompson, Robert Farris.

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Fine art and Philosophy. New York: Random House, 1983. Print.

Source: https://www.infinitemiledetroit.com/Primitivism_in_20th_Century_Art,_Affinity_of_the_Tribal_and_the_Arrogant.html

0 Response to "What Is Primitivism and How Did It Affect the Art of the Early 20th Century?"

Post a Comment